Seeing the play in French in 1898, Max Beerbohm wrote that “to translate it into English were a terrible imposition to set any one” and even Henry James, who admired Rostand, wrote of “his merciless virtuosity of expression”. Mention of Burgess raises the eternal question of how to render Rostand’s poetry. Rostand’s Cyrano hates hypocrisy, defies authority and when he says – in Anthony Burgess’s translation – “You’ve no idea how bracing it is to go marching upright against a volley of venom”, I am reminded of Alceste in Molière’s The Misanthrope in his self-lacerating honesty.

But while being shamelessly romantic, Rostand’s play is also a study of a fiercely independent spirit. Henry James pointed out in 1901, discussing Rostand in The Scenic Art, that the novel “lives its hour mainly under favour of the romantic prejudice”. It is a theme that never loses its popularity: contemporary with Cyrano was Sir John Martin-Harvey’s The Only Way, based on Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities. Since Cyrano lends his poetic genius to a dim-witted rival allowing him to woo the woman Cyrano himself loves, it is one of the great dramas of heroic self-sacrifice. Photograph: Columbia/Allstarīut I suspect there are deeper reasons for its survival. But there are other reasons for its continued popularity: it has a glorious theatricality, glittering poetry and boasts a big star part that has attracted actors as various as Ralph Richardson, Derek Jacobi and Antony Sher on stage and José Ferrer, Steve Martin and Gérard Depardieu on screen.ĭaryl Hannah and Steve Martin in Roxanne, 1987, based on Cyrano de Bergerac.

As Graham Robb has pointed out, it also had a topical resonance, coming at the time of the Dreyfus affair (the scandal in which army captain Alfred Dreyfus was convicted of treason): “the soft-hearted slasher was everybody’s hero – a man with alien features who suffered for his virtues but represented the society Dreyfus was supposed to have betrayed”. So why does it endure? At its premiere, it was seen as a revolt against the prevailing naturalist drama. There was also in 2015 a gender-swapped version known as CyranA.

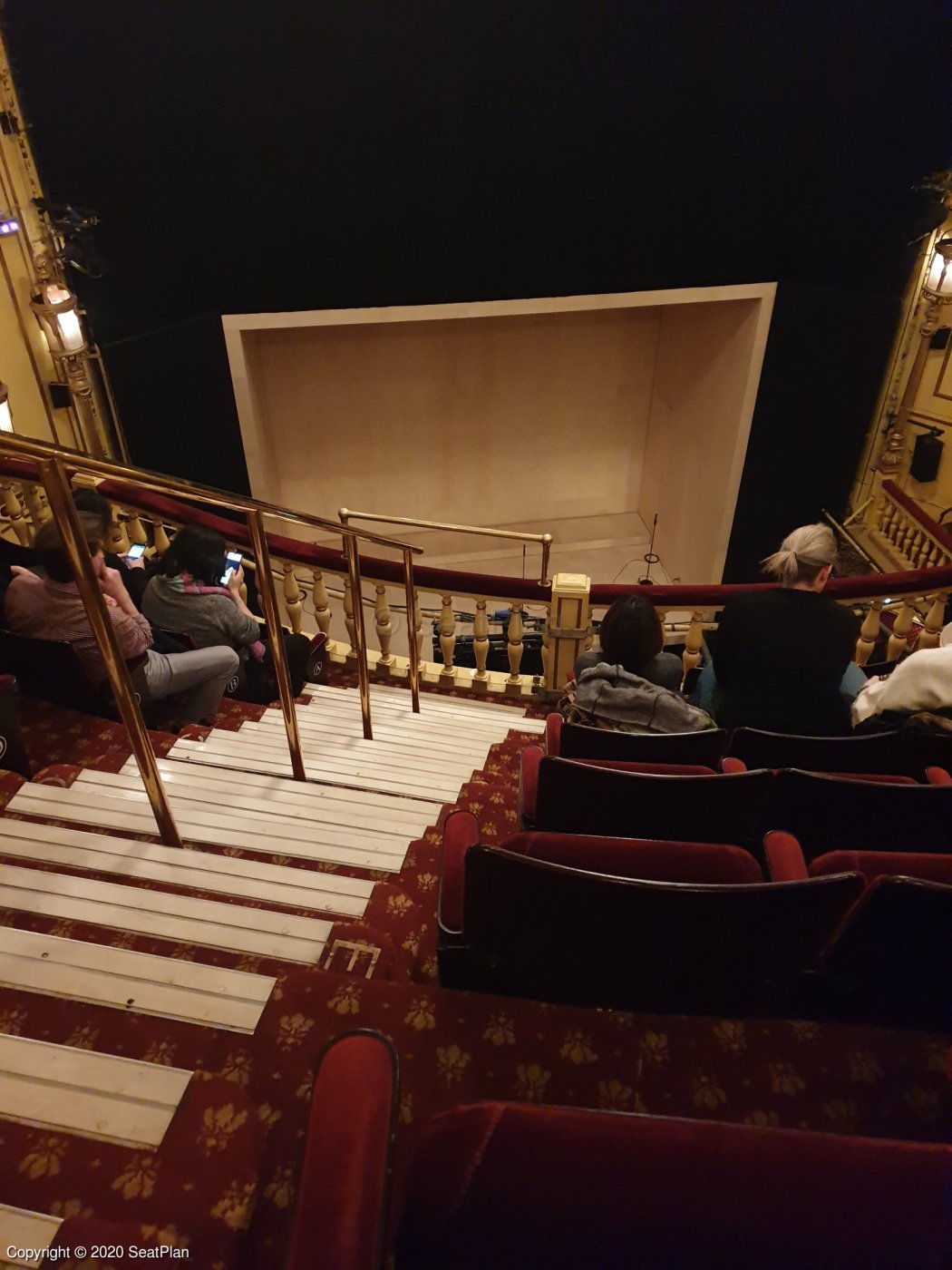

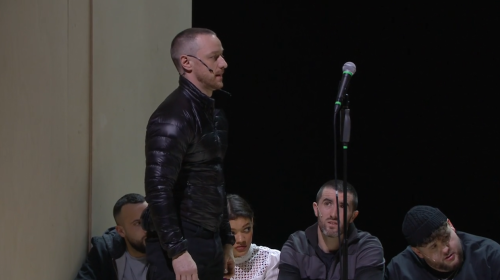

I’ve seen close to a dozen productions over the past half-century and it’s been the source of multiple movies, at least three musicals and an opera. Although in both cases the actors eschew prosthetic adornments, you could say that the noses generally have it since Rostand’s “ comédie héroïque” has been in regular revival since its 1897 premiere. Then follows the release of Joe Wright’s new movie, with Peter Dinklage in the lead. In February Martin Crimp’s radical adaptation, starring James McAvoy, returns to London, then tours to Glasgow and New York. E dmond Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac is never far away.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)